Aryan Books International,

New Delhi

ISBN 81-7305-047-3

Rs.450

Vedams Books

Having secured this valuable addition to our menial staff, our other preparations were soon completed, and at noon, on 4th July, we left Leh to cross the Kardong Pass. We were able to procure only a few riding yaks, which animal is preferred in Ladakh and other neighbouring mountain regions to the pony, as being more sure-footed, and having more endurance. Most of our equipment was carried on ponies.

The route rises continuously from Leh to the pass, situated about ten hours’ march to the north, and the last half is rough, boulder-covered and steep, which conditions, combined with the altitude, make the ascent a fatiguing one. We followed the custom of breaking the journey by encamping for the night at a spot four hours above Leh, at an altitude of 14,000 feet, from which the passage over the pass to the village of Kardong was made the next day.

At this point, we, for the first time, mounted yaks. In the course of the summer we had considerable experience with them. The yak is about as large as a medium sized ox, and resembles a buffalo, perhaps, more than any other bovine in shape. It is covered with long, glistening, black hair, which hangs from the shoulders, flanks, thighs, and tail in a shaggy profusion, that obscures all outlines. Its horns often curve forward so as to form an almost horizontal circle like those of certain beetles. Indeed, as the rider sits upon its broad back, and looks down on the massive shoulders and curving horns, he may easily imagine himself seated astride a huge horned beetle.

Its vocal utterance is a short low-pitched grunt, which, though seemingly threatening, betokens no ill-nature, for its disposition is mild. Its gait is easy, and it is very sure-footed. Moving with slow and measured tread and lowered head, the yak carefully selects a place for every step, and seldom puts its foot on an insecure stone or foothold. Often in passing boggy and treacherous places, our yaks, after examining the foot-prints of animals and men, who had preceded them and sunk in, would walk around the bad places, choosing in every case a firm foothold.

On steep mountain sides, we have seen yaks go in safety over places without a semblance of anything that could be called a path, which one would not suppose a large four-footed animal could pass, and where experienced mountaineers would tread with caution.

On the present occasion the yaks performed their part well. It was interesting to note that, although they are said in their natural state to range from 15,000 to 17,000 feet, above 15,000 feet they seemed to suffer quite as much from exertion and altitude as the human attendants, who were on foot, indeed, more so than some of them. At 17,000 feet and above, where the path was both steep and bad, only twelve to twenty steps forward could be taken without a rest, when the rapidity and force of their respiration were very marked.

We reached the top of the Kardong, 17,574 feet, towards noon, and stopped to look around. We had ascended from the south side between two mountain spurs, presenting nothing remarkable, and had encountered no snow. On the top, and for some distance down on the north side, lay a large snow-field. The view compared favourably with that from most passes. To the south, beyond Leh, some fine rock mountains were seen, while to the north three handsome snow peaks loomed up in the distance with large snow-fields, from which rose impressive snow-covered walls. These were evidently mountains in the Korakoram Range, and appeared to be at least 25,000 feet high. Snow peaks rise on each side of the pass, seemingly 1,000 to 1,500 feet above it, which looked as if they could be scaled, and from which, in clear weather, an extended view ought to be obtained.

The descent was steep and rough, over snow and rock débris for some 2,000 feet, then easier till Kardong Village was reached at 13,500 feet. On the way two small lakes were passed, one of them, just below the snow-field, being remarkable, in that the water, as seen from above, appeared to be of several colours.

Edelweiss was found on the north side of the pass at an elevation of 16,000 feet, about the highest altitude at which we have found it growing. The plant was small, the stem being from one to two inches high, and the flower, about the size of an ordinary Swiss or Tyrolean edelweiss, being of a dull green colour, with a centre of somewhat lighter shade. Also at 17,000 feet, in a wilderness of snow and rocks, far above vegetation of any kind, where nothing, that could serve as food for bird or animal could be detected, plump, well-nourished, slate-coloured pigeons, with white stripes across the wings, were flying about, evidently perfectly at home.

From Kardong Village the dusty path descends sharply, along the face of high cliffs of clay and glacial deposit of pyramidal and various fantastic shapes, to the bottom of the narrow valley, which it follows for a short distance, through a vigorous growth of tamerisk, to its opening into the broad valley of the Shayok.

We crossed the Shayok, flowing with swift current and billows two feet or more high, in a flat boat, at a point just above its junction with the Nubra River. The bed of the Shayok valley is here about 10,000 feet above sea level, and its width about four miles. Another hour's march brought us to Tsati at the opening of the Nubra Valley.

From Tsati to Changlung, some forty miles, the Nubra Valley is from two to three miles wide, and presents some features not seen everywhere in Himalayan valleys. The valley bottom is composed of alluvium, sand, and stones, over which the river flows in a broad bed with many channels and arms, which leave the main stream at various points, and soon join it again, enclosing in their course numerous islands. The river is fed by many tributary streams.

Mountains rise on both sides abruptly from the valley in great masses, forming walls of solid rock, broken only by narrow side gorges, that strike directly into the heart of the range, dividing the facing walls into enormous sections with bases miles in extent. At intervals immense tali cover the lower part of the faces of the walls to a height of 4,000 to 6,000 feet above the valley. These tali, which are the largest we remember to have seen anywhere, show the abundance of the disintegration taking place above. The tops of these walls, as seen from the valley, have been estimated at 18,000 to 20,000 feet.

The silt and detritus brought down by the floods, that pour out of the gorges, have formed very perfect and symmetrical fans, that radiate out broadly from the narrow openings, and extend to the middle of the valley or beyond.

On these fans are situated the villages, scattered through the valley at the fertile spots, where the eye is refreshed by green oases clothed with grain and grass, willow, poplar, and fruit trees. The only other instance of this fan formation on a large scale, that we have met with, is in the Shigar Valley, where it is quite as striking.

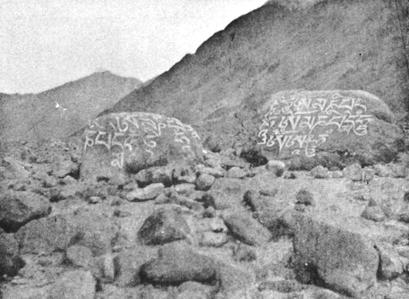

Granite mani stones near Pannamik, Nubra valley

The bottom of the valley gradually ascends, and at Changlung is about 11,000 feet. Between Tsati and Changlung, outside the villages, the trail leads over long reaches of sand interspersed with rock débris. Many streams have to be forded, some of which are impassable after midday. In a rock wilderness between Pannamik and Changlung, several large granite boulders, rounded by glacial action, are passed, whose smooth surfaces are covered with skilfully cut Om Manis, and other Buddhist prayers.

Near this point some excitement was created among the servants by the appearance of a wolf, which trotted away, just ahead, over a sand waste. This was the only wild animal of any size, excepting jackals, that we saw during our wanderings of that summer in the mountains of Ladakh, Nubra, and Suru. This, together with the fact, that few of the sportsmen, we met, had any trophies worth mention to show, seemed to indicate, that large game is becoming scarce in these parts of Kashmir.

The lack of game here recalled to mind some of our observations when cycling in the mountains of Sicily in 1893. We met everywhere sportsmen with fowling-pieces, indeed so many, that the chase appeared to be a national amusement, but we saw no winged creature larger than butterflies for them to expend their powder on. In their zeal these Nimrods had exterminated, apparently, even the sparrows. The birds, which were occasionally served at meals were so diminutive, that we were obliged to put on our eye-glasses to distinguish whether the objects on our plates were birds or insects. As the enjoyment of birds of this class is somewhat proportioned to their size, it might be found to be an advantageous gustatory expedient, when one is obliged to eat them, to deceive the palate by, the use of magnifying glasses.

At Changlung, the upper route over the Sasser Pass to Yarkand and Central Asia, one of the highest trade routes in the world, and open less than three months in the year, leaves the Nubra Valley and strikes up the steep eastern mountain wall. This route passes through a grand Himalayan region. From it can be seen, it is true, none of the four chief giants, but mountains of the respectable height of 21,000 to 25,000 feet lie all around, and present a complex of form, outline, colour, tali, precipices, glaciers and moraines, desert river valleys and yawning chasms, that can fully satisfy the demands of the most exacting human mind for the beautiful, majestic, and sublime.

As the route for several marches passes through a perfect desert, Mr Paul was commissioned to buy sheep, fowls, and a plentiful supply of eggs. The advisability of taking wood also with us was suggested to him, but he said that was not necessary, as we should find boortsa, an aromatic shrub, at all camps, and this would serve us for fuel.

On the morning of 9th July, we left Changlung. The path led directly up the steep incline, zigzagging among rocks and projecting boulders in the most tortuous manner. Our baggage was carried by three yaks and a dozen ponies, most of the latter being angular, half-starved, wretched-looking beasts, with tempers to match their appearance. The barbarian drivers were none too attentive to their duties, and the ponies, left to themselves, were constantly throwing their loads, or jamming them one into the other, or smashing them against projecting rocks, until, after a few days of this treatment, the integrity of many of our baggage coverings became so impaired, that they could not properly protect their contents, and the amount of available camp furniture was greatly diminished.

On this route, as also previously, we noticed, that, for some unexplained reason, Mr Paul’s baggage ponies always treated their loads with great consideration, and never threw them nor smashed them against the rocks. Also, of course by accident, he invariably secured a better mount than we did, so that we frequently found it to our advantage to exchange ponies with him shortly after morning starts were made.

On this barren mountain-side, as in many other similar places in Ladakh, where not a drop of water, nor a sign of moisture or of any other vegetation could be seen, the desert monotony was often relieved by luxuriant wild rosebushes, so covered with blossoms of every shade of pink, from faintest pearl to deep crimson, that stems and branches could scarcely be detected. The toneless surroundings enhanced the brilliancy with which these beautiful colour gems flashed upon the eye.

After four hours of constant ascent, we reached a pass at a height of about 14,000 feet. Here a glorious view opened before us. To the west towered the mighty mountain tongue, which, projecting from the north, separates the Nubra from the Shayok Valley. Its lower portion, for several thousand feet above the valley, presented every variety of colour, from the café au lait of wide bands of clay interspersed among the rock slopes, through many shades of brown, grey, and red, to rich maroon and purple. From the general level of this colour complex, perhaps 20,000 feet, shot up 3,000 to 5,000 feet higher, peaks of every imaginable size and shape. Some of these were cones wedges, and pyramids of solid dark blue and purple rock, with jagged apices, whose sides were so steep that snow would not lodge on them; others of greater size, covered with eternal driven snow-fields running down into glaciers in the angles between the slopes, shone before us in dazzling splendour in the wonderfully clear air, undimmed by the slightest suggestion of haze.

Below, stretched for miles the broad Nubra Valley, barren and desert except for, here and there, an oasis of green, to relieve the dreariness of the sand flats, over which the mud-tinged river pursued its course in many streams. To the east we looked down about 3,000 feet into a valley, dismal as the Valley of the Shadow of Death, without a green thing of any kind to vary the dead desolation. Over this valley on both sides hung a series of light brown precipitous mountains, whose serrated tops rose to a height of 18,000 to 20,000 feet.

In descending into this valley, on the north side, we were obliged to pass for some distance over a steep, gravelly slope, where the path was just wide enough to place the feet. It seemed as if the shifting gravel might at any moment slide away from under us, precipitating us to the bottom of the valley far below. This place might be dangerous to any one inclined to giddiness. The path led some miles further along the river over sand, rocks, and through water to Tutilak, a meadow covered with short grass, on the river bank, at the foot of a large glacier, where we encamped.

The following day we ascended between grand mountain walls to the foot of the Sasser Pass, and encamped on a small piece of meadow covered with short scrubby grass, at a height of 15,600 feet. This spot, like the whole region we had traversed for the last two days, was surrounded by vast mountains of wild and rugged grandeur, while in front the end of the huge Sasser Glacier rose before us.

The temperature had now become chilly, 40 degrees Fahr., and the wind uncomfortably strong. We ordered the cook to bring hot water for tea. He soon appeared minus the water, holding in his hand several pieces of rubbish and dried grass picked up near by, which he mournfully said was all the fuel that could be obtained, turning them meanwhile with a disgusted expression from one hand to the other, and the supply of these was limited. He had not been able to heat any water.

Mr Paul was at once summoned and asked, where the boortsa was, which he had promised. He replied they had not been able to find any here. Calling to mind the oft quoted remark about not trusting an Indian, we duly reprimanded him for his negligence and told him, to send out coolies to collect as much of the first named apology for fuel as possible, to cook the dinner with, and to send back for boortsa or wood.

Toward evening the wind increased, till it blew almost a gale, so that the khansamah was obliged to make his oven for cooking the dinner inside his tent, which was soon filled with the suffocating smoke of the wretched fuel. As a result not only the soup, meat and other viands, but even the plates and drinking cups were so strongly impregnated with the pyroligneous odour, as to destroy all satisfaction with the meal.

During the night the temperature fell to 30 degrees Fahr., and there was a considerable fall of snow. The cold together with the altitude caused the death of several of the fowls, which fact did not trouble us greatly, as, on investigation we found all those furnished by the Lambardar or village chief at Changlung, were game cocks with spurs over an inch long, indicating an age which rendered them useless for anything but soup. Also one of the ponies, which was ailing the day before, died, but we were, fortunately, able to replace him the next morning by a yak—called by Mr Paul a jungle yak—that was wandering without any master on the mountain-side.

The path to the pass winds up the steep terminal moraine of the glacier to a high overhanging wall of ice, under which it runs for a short distance and then ascends on the lateral moraine, from which ever and anon large stones come rolling clown. One passes under that overhanging wall with an uncanny feeling and keeps a sharp look-out for stones from above. Then the path leads on to the glacier itself, over places so covered with rocks and detritus, that no ice can be seen, through ice ravines with small rivers flowing along their bottom, up and down over ice hillocks, into valleys, past ice lakes, till, finally, after a three hours’ climb, it brings one to a vast field of ice and snow covering the whole space from the mountains on one side to those on the other. A short scramble up the steep side brings one to its upper surface, comparatively smooth, where the grade is easy for the next mile. Then comes a descent again to the lateral moraine, and another steep ascent to the glacier, at the top of which the highest point, 17, 500 feet, is reached.

From the valley below, over the pass and on to Sasser, both sides are walled in by gigantic ragged peaks, seamed and rent by enormous chasms, which with the glacier and moraines form a grand though desolate picture. Behind, towards the west, is a group of snow mountains, from 21,000 to 25,000 feet high, of impressive size and beautiful shapes. The descent to Sasser, 2,000 feet below, is of about the same nature as the ascent.

The day was cold and the wind strong and biting. When we reached the top of the pass we sought the shelter of a large boulder near the middle of the glacier, which afforded partial protection from the wind, drew our Tyrolean lodens closer around us and ate our tiffin, after which our Ladakhi attendants eagerly seized the empty tins. These pig-tailed Mongolians, as well as other natives of the North, gladly appropriate empty food tins, bottles, pictures and tin foil from chocolate, and other stray bits from the tiffin basket. The tins and bottles fill a very important place in the domestic economy.

From Changlung over the Sasser Pass and down to Sasser, a three days’ journey, the pathway is strewn with many fresh carcasses, and the bleaching skeletons of thousands of ponies fallen by the way. These afford plenty of occupation to the vultures, which strip the bones of every particle of soft substance, leaving them white and clean. Any one desiring to investigate the bony anatomy of the pony could not do better than to encamp for a few weeks in this equine graveyard, where abundant material for study and comparison may be had ready at hand.

In some places these skeletons cover the ground in groups of twenty to fifty, in much the same manner as might be seen after a severe battle, at points where cavalry or artillery have been stationed, and, lying in various attitudes, present a ghastly spectacle unpleasantly suggestive of what sometimes happens, under certain circumstances, to human beings also in this elevated desert. We saw no human skeletons, but an Englishman, who had been over the route, told us he saw two.

Scarcity of food, the exhaustion caused by the difficult paths, cold and the tenuity of the air at this elevation prove fatal to many caravan ponies during the three months this route is open. The greater part of the trade to and from Yarkand and Central Asia passes over a lower and longer route. Cold storms and a freezing temperature may overtake the traveller over the Sasser at any time, and he, who comes here, must be provided for these exigencies.

The route after Sasser passes over Branga Sasser in three marches to the Dipsang Plateau, 17,800 feet. Thence the Korakoram Pass, 18,300, is reached in two marches. The chief interest of the route after the Sasser Pass is, the height at which one is travelling, and the uninhabited plain. The scenery reaches its culmination on the Sasser.